In this article, we delve into the shifting attitudes, both internally and externally, influencing the rise of Japanese players moving to Europe.

These players have only just started appearing for the national team but there are many that have not: "Nowadays, even if you're not in the national team – or even a regular starter in the J.League – it's becoming normal to move abroad," said Tanabe Nobuaki, a players' agent.

At the start of the European season, it was reported by national broadcaster NHK that there were 114 Japanese players in European teams, with over 60% of these players moved before gaining national team experience – reinforcing this significant shift away from traditional routes mentioned by Nobuaki.

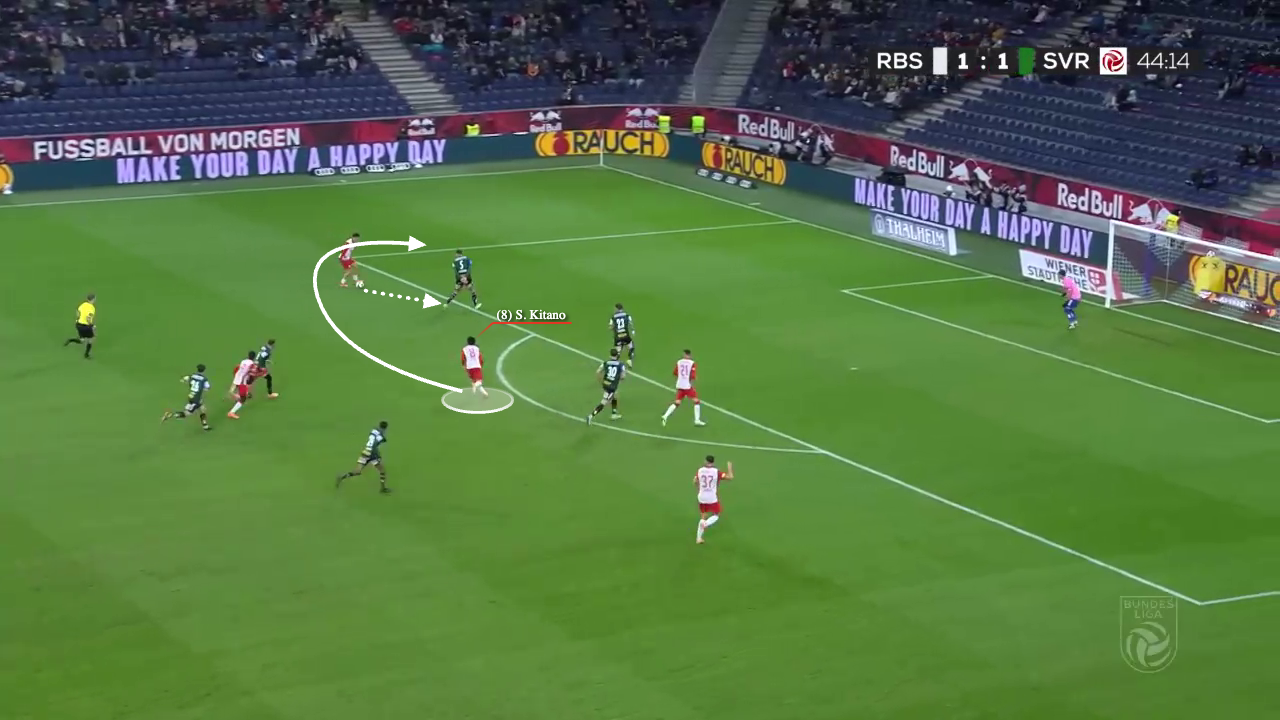

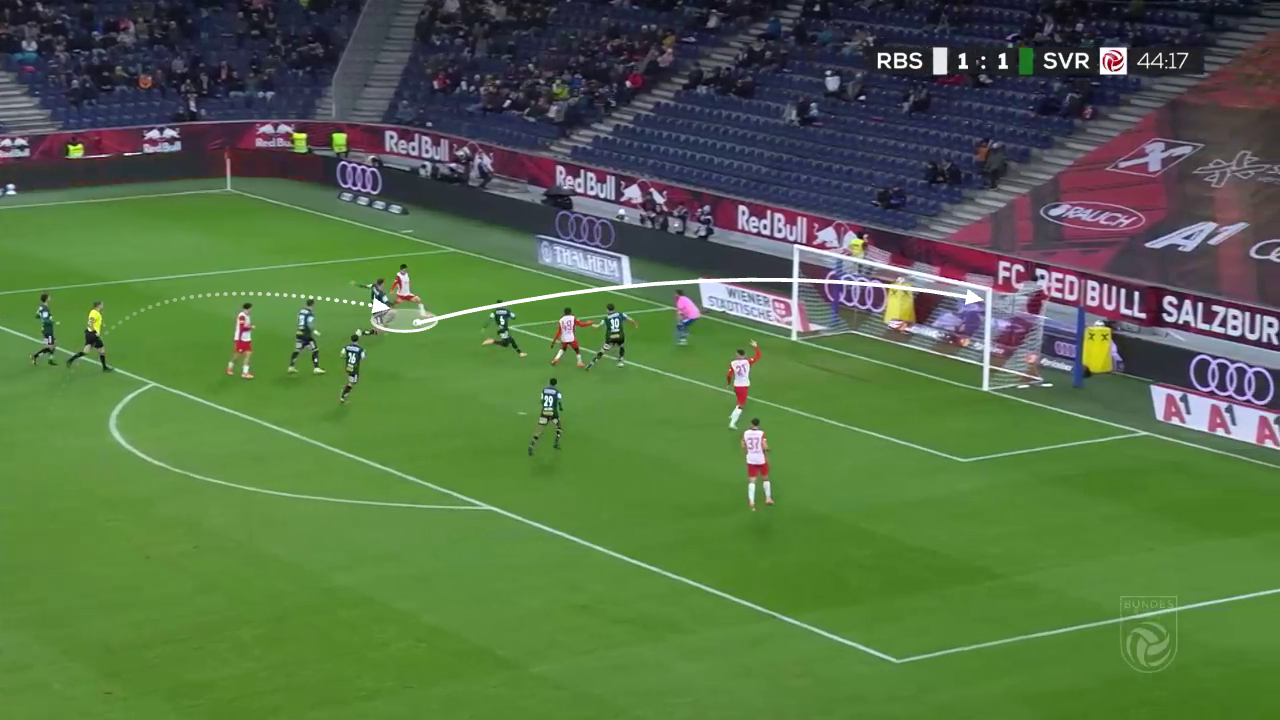

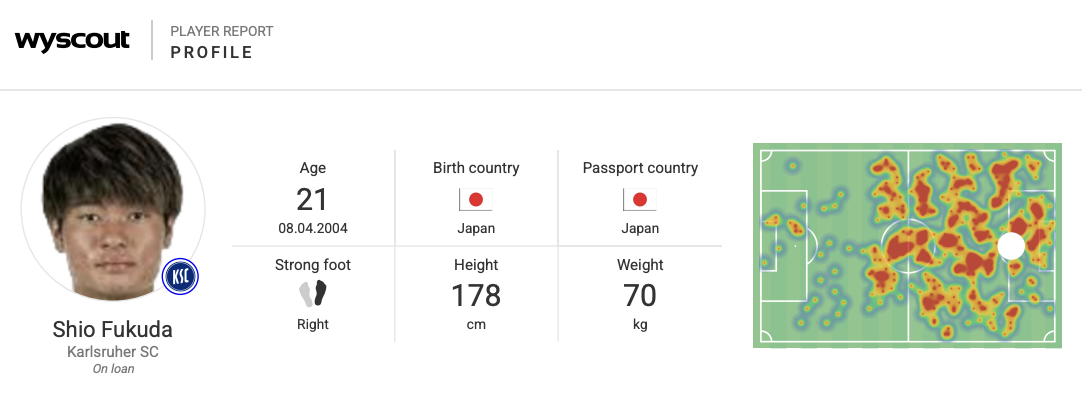

A prime example is Shiō Fukuda, who was picked up by Borussia Monchengladbach straight from Kamimura Gakuen High School, having not played a minute of professional football in Japan.

The consequence is a pipeline which sucks in players who are barely out of their teens and sometimes not even that. This shift isn’t simply about leaving Japan; it’s about faster growth, better coaching, and earlier chances to prove themselves at the international level.

This has not come out of nowhere. Japan has the best youth development in Asia and one of the best anywhere. It is built upon the schools and universities, which have long played a part — the country’s high school championships are a national event and broadcast on television with crowds sometimes reaching 50,000.

In more recent times, professional clubs and private academies are getting more and more involved. There is also a culture that values practising and training, not just every week but often every day.

Stronger youth academies, improvements in coaching standards, and broader adoption of data-driven development give players a more solid foundation before they even consider leaving to faraway destinations. With better youth leagues, clearer progression ladders, and more professional youth exposure, Japanese prospects can mature with a more global outlook.

European scouts increasingly come into contact with players in the U15–U17 window, sometimes inviting them to overseas academies or offering pathways into club systems with defined progression routes. This mutual influence—Japan lifting its own development while Europe broadens its talent net—creates a more predictable and faster route for young talents to move overseas.

As a result, the cross-pollination accelerates, expanding Japan’s footprint in global football networks while giving European clubs access to highly technical, tactically flexible players.

Where are the preferred destinations?

In the early 21st century, Germany emerged as a preferred landing spot in Europe, partly because there were agents there that were familiar with Japan and a tried and trusted pipeline was soon established. This ongoing pipeline reduces scouting risk and helps clubs build relationships with Japanese agents, youth coaches, and clubs.

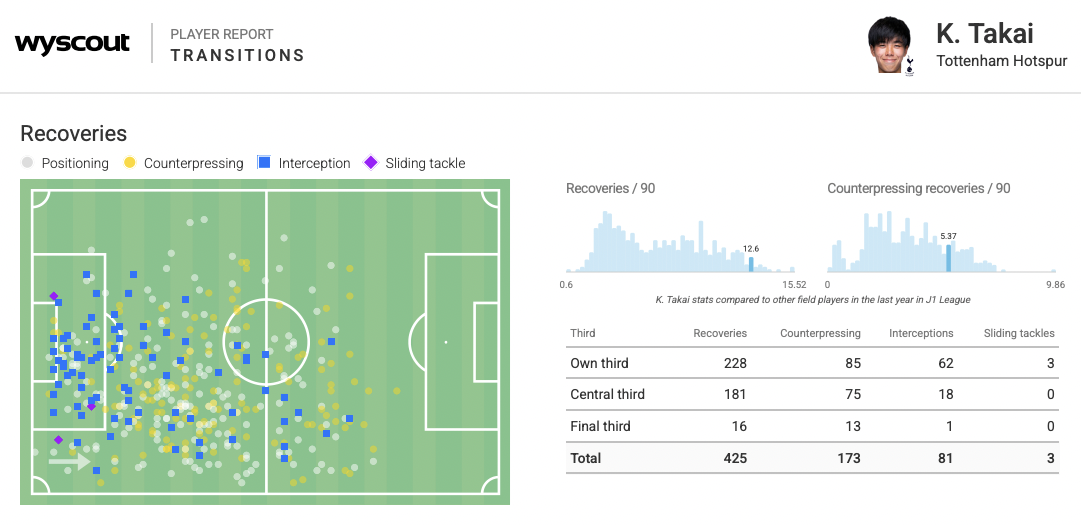

The network has extended to other nations, and we have seen players move directly to clubs in the English Premier League such as Kaoru Mitoma to Brighton in 2021 and Kōta Takai to Tottenham Hotspur in 2025.

A look at Wyscout viewing data, shows that over the past three years Belgian clubs have consistently had the highest numbers of clubs among the most frequent viewers of the J.League.

Unsurprisingly there have been a number of Japanese players moving to the Pro League: a gateway landing spot ever since 2017, when Japan’s DMM Group acquired Sint-Truiden VV. As such, De Kanaries, now part-owned by another Japanese company Japanet Holdings, have been the launchpad for many players making their first steps in Europe, such as goalkeeper Zion Suzuki.

The numbers also show a steady increase in interest from Danish clubs, also reflected in transfer strategies of Brondby and FC Kobenhavn, and 2.Bundesliga teams searching for good value.

It’s also noteworthy to see clubs from Serbia, Poland, the United States, Scotland among the top viewers, with an increasingly diverse range emerging, as represented by interest ranging from Mexico and Brazil to Sweden and Greece. Notable by their absence are top teams from Spain and Italy – pointing to a potential gap in the market for forward-thinking clubs looking to gain a competitive advantage.

Why clubs like Japanese players

Firstly, in terms of technical ability, there are few better. Japanese players almost always have elite ball control, precise passing, and a fine understanding of pressing and defensive structure that fits modern European systems. This technical foundation helps them integrate quickly into diverse leagues and coaches’ philosophies.

It is a little stereotypical but there is a strong mentality and sense of professionalism. This disciplined work ethic, resilience, and willingness to learn are repeatedly cited as hallmarks of Japanese players. European clubs prize players who can handle intense travel schedules, media scrutiny, and the demands of top-tier competition without significant off-field disruption.

And then there are the simple economics: Transfer fees for top Japanese talents have often been relatively affordable compared with established European stars, offering good value for money. In addition, long-term potential and resale value can be appealing to clubs operating within tight wage structures and budget constraints

There has even been criticism, going back a few years now, that clubs in the J League do not get the fees they should and undervalue their talent. The reported $7 million or so that Kawasaki Frontale received for Takai was a record for a Japanese player leaving the J.League and was seen as a step in the right direction.

The J.League’s response

The exodus of more and more players can be a double-edged sword. There is no doubt that it has presented challenges for J.League teams. In AFC continental club competitions, it has perhaps blunted their competitiveness to an extent.

Yet until the last eight, the tournaments are divided into geographic zones and Japan can compete with rivals from China, Korea and Australia anyway. The big-spending Saudi Arabian clubs are a different and much tougher proposition, but that would be the case if Japanese teams held on to their talent for longer anyway.

In May, Kawasaki reached the final but could not get past the star-studded Al-Ahli. Yokohama F.Marinos did the same in 2024 and Urawa were champions in the tournament before that.

Going forward

We’re likely to see more of the same. As the J.League continues to sharpen its academy networks and deepen overseas partnerships, Europe will keep welcoming a steady stream of technically adept players. The Japan–European football relationship will keep evolving.

In short, Japan are producing lots of exciting and talented young players and this is now recognised around the world. Not all succeed and those that don't can return home having learnt from the experience. But there are enough that do impress to ensure that interest remains high. Another good showing at the World Cup next summer will only increase that interest.

The story isn’t finished, but the themes are there for all to see: a dynamic, interconnected ecosystem that challenges and strengthens Japan’s football identity on the world stage.

Ready to transform your recruitment process? Find out more about how to use Hudl Wyscout for your scouting, recruitment, and talent evaluation workflows here.

Follow John on Substack.